Colonial First State Senior Investment Manager, George Lin, explains how the Coronavirus pandemic affected markets through the quarter to March.

Financial markets entered 2020 with optimism, following the announcement of a highly anticipated Phase 1 trade agreement between the US and China in early December. Trade tensions, which cast a dark cloud over the global economy in 2019, quickly dissipated. Financial conditions were also easier after three reductions in policy rates by the Federal Reserve in 2019. Investors were in full risk-on mode and equity indices continued to rise.

At this time, little attention was paid to reports of an unusual respiratory disease in central China. However, the news became more alarming when the Chinese government announced a lockdown in the city of Wuhan in mid-January – followed by a nation-wide lockdown only a few days later. Asian markets reacted negatively to the news, but markets across the rest of the world barely budged – reinforced by a false sense of security that travel restrictions on movements from China, imposed by governments such as the US and Australia, would contain the then-unknown virus – earlier referred to as the Wuhan Coronavirus.

Italy was one of the first countries to impose travel restrictions on China, but by early March, still reported more than 10,000 cases. The Italian government was forced to impose a lockdown on Lombardy, the worst affected region, followed quickly by a national lockdown. The same scenario – that is, a soaring number of new cases, fear of the health system being overwhelmed, and the introduction of extreme social distancing measures to “flatten the curve” – was quickly repeated in other countries, first in Europe and then in the US. And by week beginning 23 March, most of the developed economies (including Australia) were in different phases of lockdown. The world was experiencing its first Coronavirus pandemic.

A global economic slowdown

The lockdown in China was a significantly negative supply shock to the global economy – particularly given the importance of China in the global supply chain of a number of industries, including automobiles, telecommunications and computers. As China has begun to lift various restrictions over the past fortnight, greater visibility on the economic impacts of the Coronavirus have been revealed. Market consensus is that China will have negative GDP growth in the March quarter, followed by a modest recovery and annual GDP growth of between 3.5% and 5.0% in 2020. Such an outcome would represent the lowest level of GDP growth for the region since early 1990s, yet may be optimistic.

The outlook on the other developed economies including Australia is less visible, since most countries are still in the relatively early stages of the Coronavirus cycle – and are possibly weeks (or even months) away from lifting some of the restrictive policies. Nonetheless, there are several key observations markets have made:

- The unprecedented restrictive measures announced by various governments represent a massive negative demand shock to the global economy. Most developed economies are relatively consumer-driven and services-oriented, and are therefore highly exposed to the negative economic impacts of social distancing. The lockdown policies have represented a significant negative supply shock, and have reinforced the negative supply shock from the Chinese shutdown. Many businesses worldwide, particularly in the hospitality, travel and aviation sectors, are now facing severe cash flow problems.

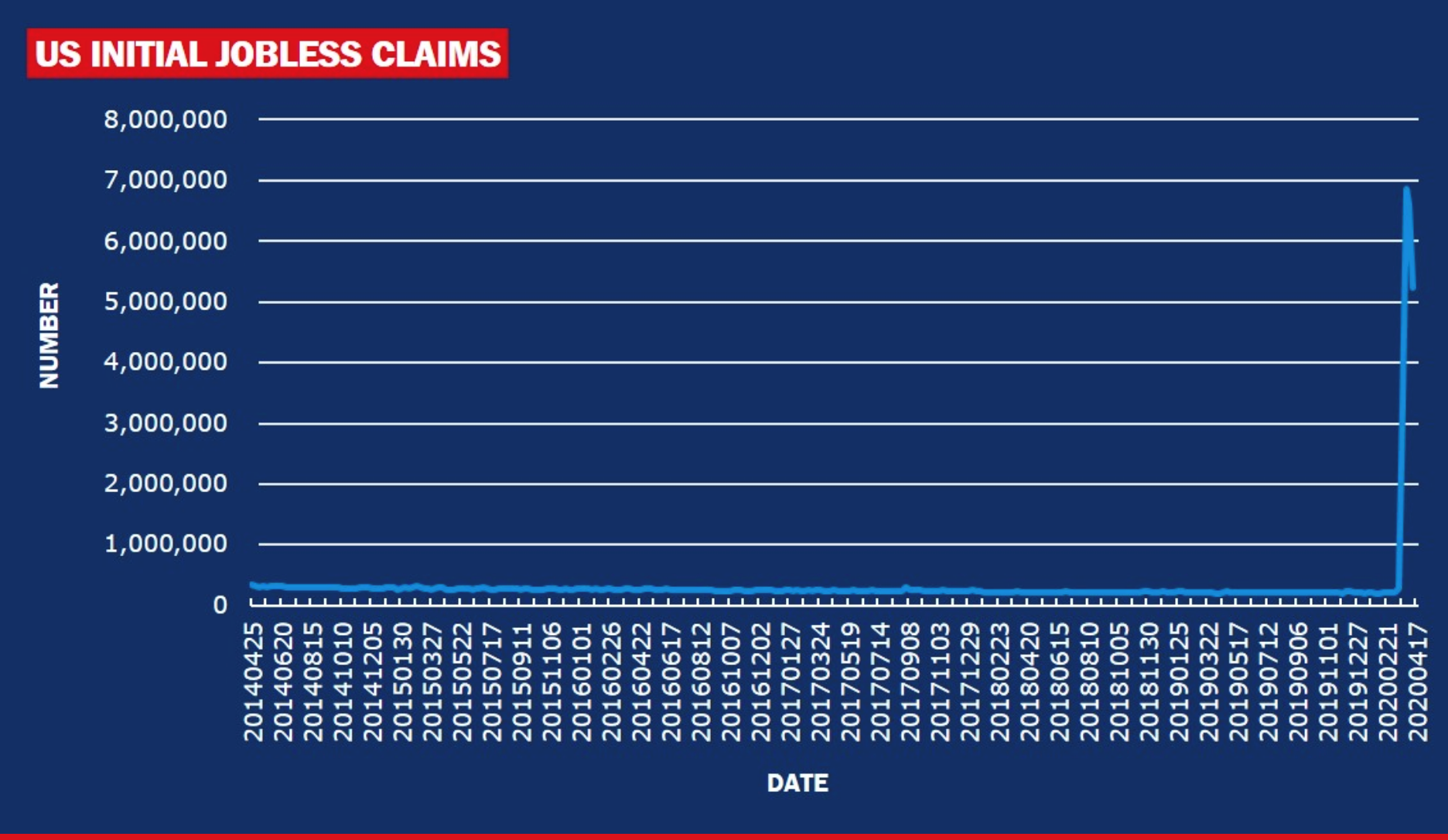

- We are beginning to see the economic impacts of the lockdown through economic statistics. As you can see in the chart below, by the end of March, the number of weekly initial claims for unemployment benefits in the US sky-rocketed from 282,000 to 6.6 million within two weeks. We can expect more negative headlines about economic data over the coming weeks.

- Virtually all policymakers and economists now expect a significant decline in global and Australian GDP in the June quarter. The debate centres on the duration of the economic downturn, as well as the magnitude and timing of an economic recovery – both of which are highly dependent on Coronavirus developments. The consensus seems to be that governments will start lifting some of the containment policies, albeit in a gradual manner, from late May to June. The bottom of the global economic cycle will be reached sometime in the September quarter, followed by a recovery. In summary, the world and Australia will have a sharp but relatively short technical recession.

Policy responses by central banks and governments

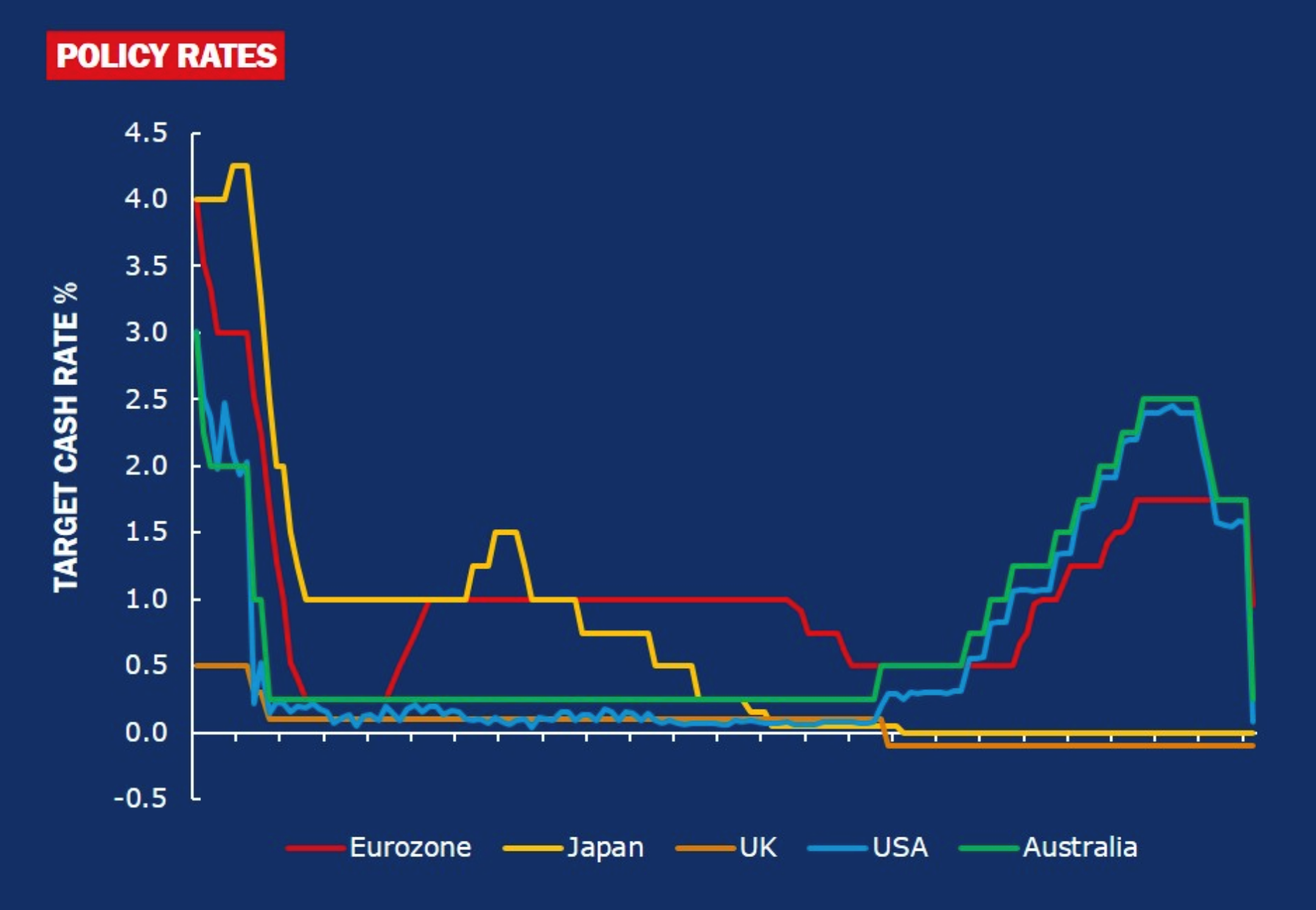

World central banks attempted to support their respective economies in two ways. Firstly, they reduced their target policy interest rates to nearly zero. Secondly, all the main central banks have announced quantitative easing programs to purchase large quantities of securities – mainly government or government-related bonds – in the secondary markets.

In Australia, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) reduced the official cash rate to 0.25% in March, and committed to not to increase the cash rate again “until progress is being made towards full employment” and until it is “confident that inflation will be sustainably within the 2–3% target band”. The RBA also announced its own quantitative easing program and adopted a bond yield target of 0.25% for the yield on 3-year Australian Government bonds. This means the RBA is prepared to purchase government bonds in a sufficient quantity, whatever the level may be, in the secondary market to drive the yield on these bonds to around 0.25%.

A quarter to remember (but for the wrong reasons)

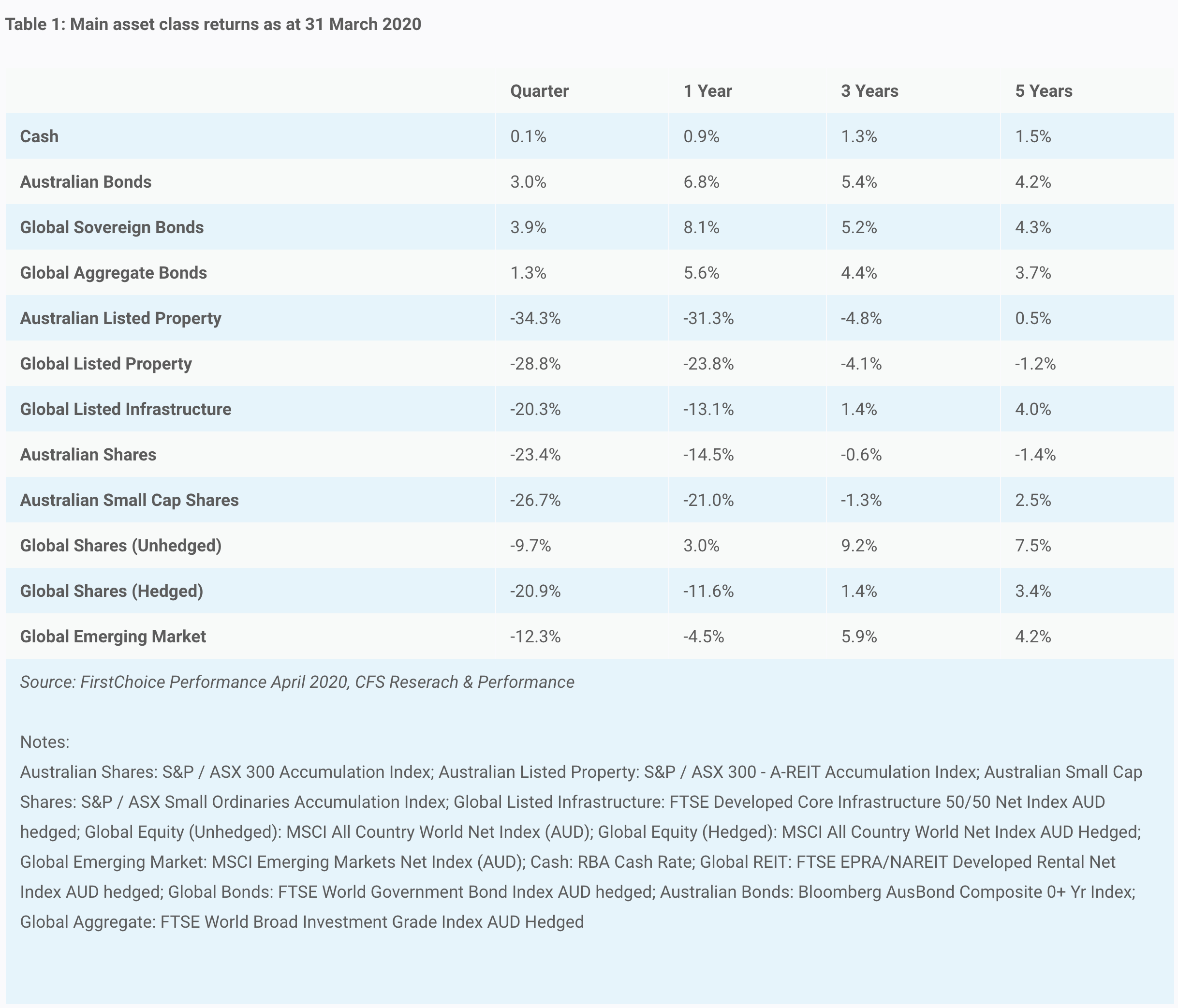

All growth asset classes, in particular shares, recorded sharp declines in the quarter due to the global economic impacts of the pandemic. All investments were impacted over the quarter, with the level of volatility increasing sharply across all asset classes.

- Australian bonds returned 2.99% and global sovereign bonds returned 3.91% in the March quarter, as bond yields fell during this time. US 10-year Treasury bond yields started 2020 at 1.9%, reached a low of 0.50%, and then finished the quarter at 0.68%. Australian 10-year bond yields followed a similar pattern – ending the quarter at 0.76%

- The strong returns from sovereign bonds masked the weakness in corporate bonds. The global aggregate benchmark (which comprises almost 40% corporate bonds and securitised assets) returned 1.27%, as spreads on corporate bonds increased sharply in March.

- Australian listed property and global listed property had a torrid quarter, returning -34.31% and -28.80% respectively. The retail sector was particularly hard-hit as social restrictions dramatically reduced the number of shoppers worldwide.

- The Bull Run in share markets came to an abrupt end. The Australian share market fell by 23.41% in the quarter, wiping out the gains in the All Ordinaries Index over the past three years. The main overseas share markets also recorded significant falls, with the MSCI All Country World Index returning -20.94% (on a hedged to the Australian Dollar (AUD) currency basis).

- The sharp decline in the AUD provided some downside protection to investors in unhedged global shares. The AUD declined from 0.70 USD to 0.61 USD by the end of March. As a result, the MSCI All Country World Index returned a more respectable -9.04% over the quarter.

George Lin is a Senior Investment Manager at Colonial First State